Keep It All Inside

JEFF HALSTEAD & DANNY KARAS

Sir. John Soane Museum, London, England

Professors: Hernan Diaz Alonso with Ivan Bernal

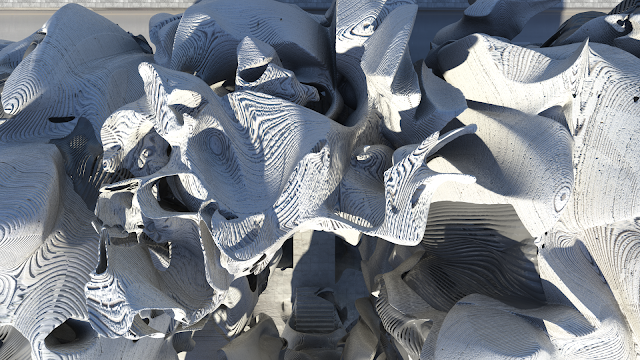

Carving in architecture is typically subjected to material that is quite homogeneous in relation to the scale in which it is buildable (carving out a marble column).

Cutting out portions of material from a preexisting heterogeneous mass offers a very disparate method to producing constructible material. In this case, the scale of material already has form. Because of this and unlike that of a marble column, cutting up the material is not the only way a designed figure derives its form.

Two different sophistically detailed primitives serve as the base objects in which cuts are made and chucks removed from. One primitive is hard and porous in nature; the other is soft and fatty.

Certain constraints like weight, porosity and enclosure all influence the location and direction of each cut on the primitive. The topology of each cut is in relation what part of the initial object is being cut and where the removed piece will be situated against the others. There could be larger cuts through some of the more porous areas and smaller cuts along the thicker more massive areas. This allows for a certain level of control over the outcome, but is ultimately subjected to the character of the initial mass in which it was cut from. After a series of these chucks have been carved out, they are assembled together.

The result is a miscreation, neither a complete deliberately designed thing nor the unauthored original object it stemmed from.

Shaping form in this manner changes the relationship of material to the thing it embodies. Now, instead of the architectural model serving as a reference to build from, it is a stage in which model and material are of the same process. Different chunks are continually being dismembered, combined, left in place or removed again - constituting a process of production based in deformity.

.jpg)

.jpg)